The numbers were even worse in investment banks (though that industry is shrinking, which complicates the analysis).

commercial banks who were Hispanic rose from 4.7% in 2003 to 5.7% in 2014, white women’s representation dropped from 39% to 35%, and black men’s from 2.5% to 2.3%. Although the proportion of managers at U.S. But on balance, equality isn’t improving in financial services or elsewhere. They have also expanded training and other diversity programs. It’s no wonder that Wall Street firms now require new hires to sign arbitration contracts agreeing not to join class actions. Cases like these brought Merrill’s total 15-year payout to nearly half a billion dollars. In 2013, Bank of America Merrill Lynch settled a race discrimination suit for $160 million. In 2007, Morgan was back at the table, facing a new class action, which cost the company $46 million. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Morgan Stanley shelled out $54 million-and Smith Barney and Merrill Lynch more than $100 million each-to settle sex discrimination claims.

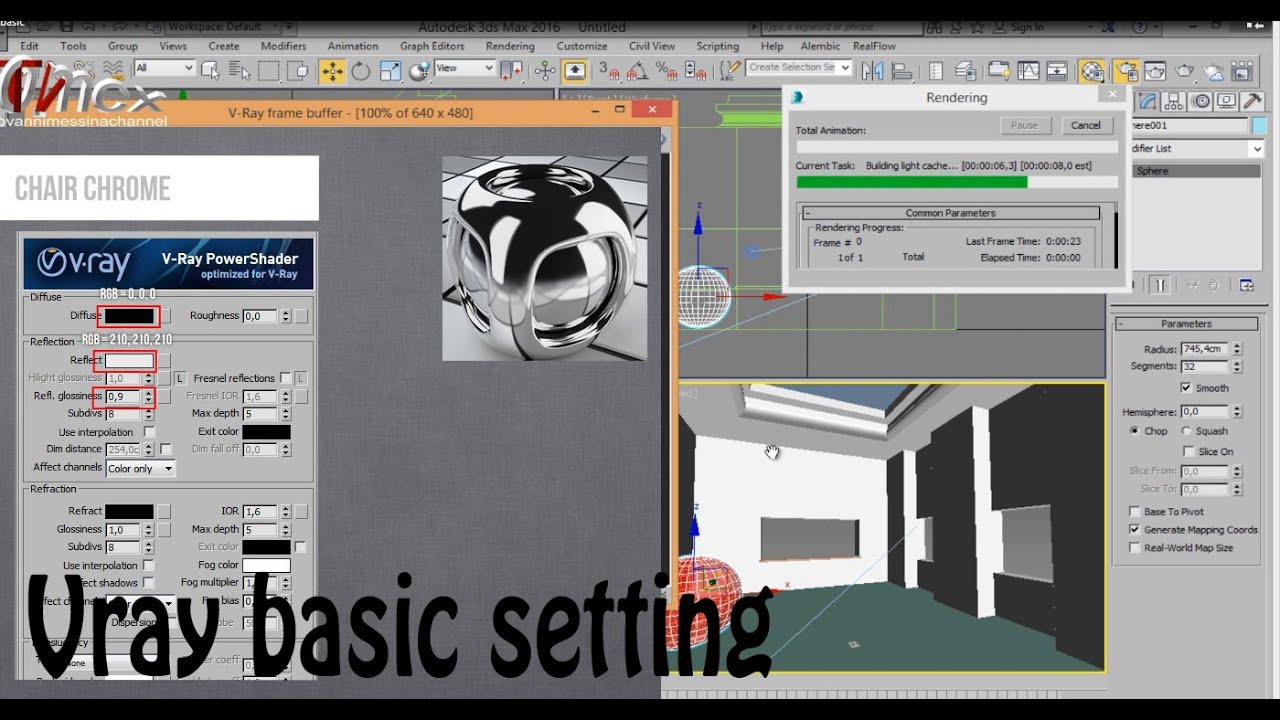

#Why does everyone use vray 2016 series

Instead of trying to police managers’ decisions, the most effective programs engage people in working for diversity, increase their contact with women and minorities, and tap into their desire to look good to others.īusinesses started caring a lot more about diversity after a series of high-profile lawsuits rocked the financial industry. People rebel against rules that threaten their autonomy. Most diversity programs focus on controlling managers’ behavior, and as studies show, that approach tends to activate bias rather than quash it. Some of these efforts make matters worse, not better. To reduce bias and increase diversity, organizations are relying on the same programs they’ve been using since the 1960s. In this article, the authors dig into the data, executive interviews, and several examples to shed light on what doesn’t work and what does. They engage managers in solving the problem, increase contact with women and minority workers, and promote social accountability. However, in their analysis the authors uncovered numerous diversity tactics that do move the needle, such as recruiting initiatives, mentoring programs, and diversity task forces. But as lab studies show, this kind of force-feeding can activate bias and encourage rebellion. They’re designed to preempt lawsuits by policing managers’ decisions and actions. The authors’ analysis of data from 829 firms over three decades shows that these tools actually decrease the proportion of women and minorities in management. And the usual tools-diversity training, hiring tests, performance ratings, grievance systems-tend to make things worse, not better. The problem is, organizations are trying to reduce bias with the same kinds of programs they’ve been using since the 1960s. But unfortunately, they don’t seem to be getting results: Women and minorities have not gained much ground in management over the past 20 years. After Wall Street firms repeatedly had to shell out millions to settle discrimination lawsuits, businesses started to get serious about their efforts to increase diversity.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)